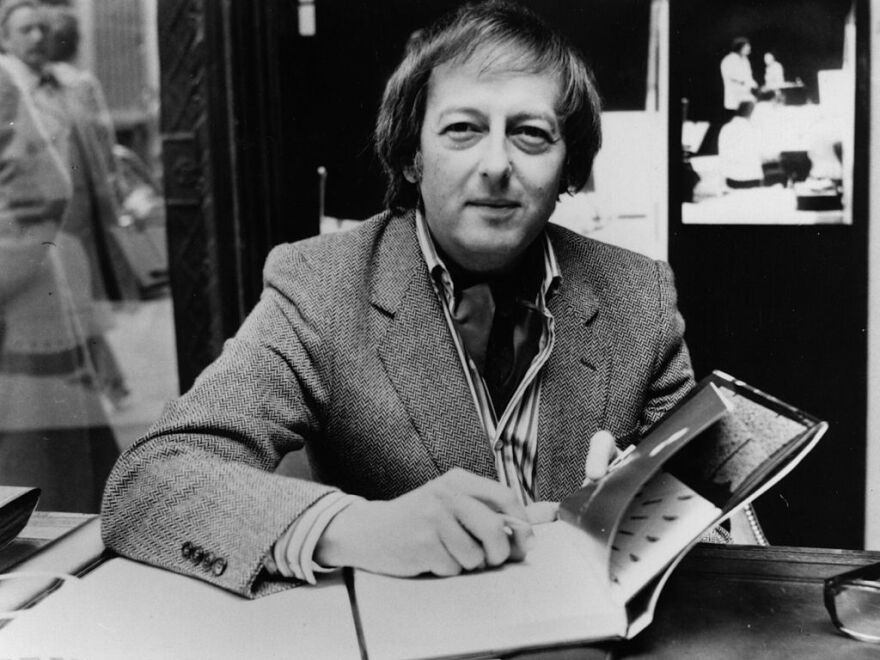

André Previn, a celebrated musical polymath, died Thursday morning; he was a composer of Oscar-winning film music, conductor, pianist and music director of major orchestras. His manager, Linda Petrikova, confirmed to NPR that he died at his home in Manhattan.

Previn wrote a tune in the 1950s. In the vernacular of the day, he called it "Like Young." His Hollywood friend, the great lyricist Ira Gershwin, was critical. "Don't you know it should be "AsYoung?" asked Gershwin. Previn loved that story — from his jazz side.

Tim Page, a Pulitzer Prize-winning former music critic and professor of journalism and music at the University of Southern California, says that jazz was just one side of the multitalented artist. "He really seriously distinguished himself in a lot of different fields. He was not one of these people who came in and shook up one field forever and ever," Page notes.

Previn began his musical life "like young." Born in Berlin on April 6, 1929, as Andreas Ludwig Priwin, he grew up in Los Angeles. His family fled Germany in 1938 and first moved to Paris, and then New York, before landing in Hollywood. As a wunderkind teenager, he played piano at the Rhapsody Theatre, improvising scores at silent film screenings.

"There was one of those huge silent epics which kept vacillating allegorically between biblical times and the Roaring '20s, and so I really had to pay attention," Previn told NPR's Weekend Edition in 1991. "But I noticed that each time they switched venues, as it were, it would stay there for a while. So we came out of a biblical time and back into people Charlestoning their life away. And I thought, 'Well, I'm safe for a few minutes.' And so I started playing 'Tiger Rag,' and I heard a commotion in the audience, and the manager was storming down the aisle. And I took a quick look up on the screen — and I was playing 'Tiger Rag' to the Crucifixion, which was a bad choice. And I was out on the pavement about three minutes later."

When Previn was 16, in 1944, MGM hired him to work on scores for talking films. His book No Minor Chords is full of stories about those Hollywood years. Page remembers one about the notoriously difficult Cleveland Orchestra conductor George Szell, who wanted to see how Previn would play with the orchestra.

There was no piano at hand. So, in Page's recounting, Szell said: "Play it on that tabletop."

Ridiculous, thought Previn. But he went ahead. Then Szell started giving directions: "Slower. Faster. More tender. It went on and on like this," says Page. "And finally Previn had had enough, and said, 'I'm sorry, Maestro. My tabletop at home has a much different action.' "

Szell threw him out. Previn went back to making music on real instruments — and writing it, too. He composed chamber music, concertos and operas, including his 1998 setting of Tennessee Williams' play A Streetcar Named Desire.

Streetcar premiered in San Francisco, with soprano Renée Fleming playing Blanche DuBois. The composer once told NPR's Robert Siegel on All Things Consideredhow he readied for responses to his new work.

"Well, I prepared myself by rereading the reviews, for instance, of the opening of Carmen," Previn said to Siegel, referring to the infamous debut of Bizet's now classic opera.

"That was a disaster, apparently. A flop." responded Siegel.

"Oh, yeah. Total," Previn admitted.

(European critics liked Streetcar; U.S. reaction was mixed.)

Previn served as music director of the Houston and Pittsburgh symphonies and the Los Angeles Philharmonic, as well as principal conductor of the London Symphony and Royal Philharmonic orchestras, and appeared as a frequent guest conductor worldwide. Page says Previn could be counted on for strong performances from any podium. But that long list of Previn-led orchestras does tell you something about the conductor.

"I guess it says a couple of things," Page observes. "No. 1, it suggests that he was very interested in performing around the world, and he worked with some very fine orchestras. On the other hand, there was never that huge sort of connection with one orchestra that, say, we have with Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic, and George Szell and Cleveland."

Commitment problems, perhaps? Not only did Previn not make any married-for-life arrangements with any orchestras, but he went through five marriages. His ex-wives were jazz singer Betty Bennett, who sang with big bands including those of Stan Kenton, Woody Herman and Benny Goodman; the singer-songwriter Dory Previn, with whom he co-wrote the theme to the 1967 film Valley of the Dolls; actress Mia Farrow; Heather Sneddon, to whom he remained married for 20 years; and finally one of the world's most renowned concert violinists, Anne-Sophie Mutter, for whom he wrote his first violin concerto, which he named "Anne-Sophie." (They divorced in 2006.)

Previn won four Oscars for his film work, including his adaptation of the score for the movie version of My Fair Lady. He also won 10 Grammy Awards for his film, jazz and classical recordings, as well as a lifetime achievement prize in 2009; he was also awarded a Kennedy Center Honor in 1998. This versatile, gifted musician was so multitalented. But Page argues that his best work was far removed from the concert stage.

"As good as some of his high-classical music was," Page says, "I'm not sure he ever did any better work than he did as a jazz pianist and writing for film. And there's no disgrace in that whatsoever — I think [it's] really good jazz piano. And he was so musical, and so lyrical and so inventive — it's a real accomplishment."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDA1NTMzNDA4MDEyNzk4MTU2OTg2ZjAyZQ004))