Editor's note: This story is part one of a two-part series. To read part two, click here.

WARREN, Maine — Sometime this month the Maine Department of Corrections is expected to finalize proposed new disciplinary rules for the Maine State Prison, governing everything from prisoner communication with the outside world to hygiene, contraband and safety threats.

Inmates who break the rules face monetary sanctions, loss of good time and segregation, better known as solitary confinement.

The Maine Department of Corrections, or DOC, says it has sharply reduced the use of segregation over the past five years, but there remain concerns about the length of time prisoners are spending in virtual isolation and about lack of transparency in the process that keeps them there.

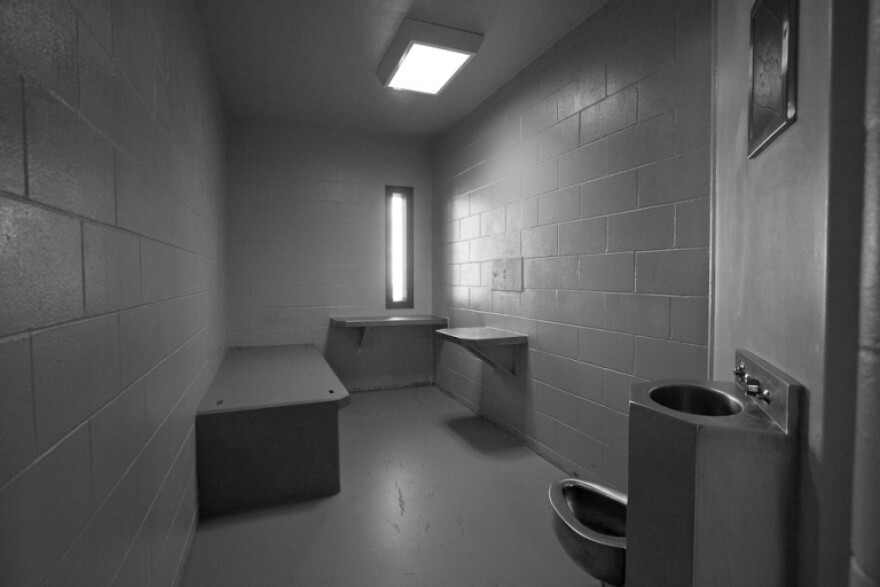

Douglas Burr is confined to a cell in the Maine State Prison that he describes as about 8 feet wide and 10 or 12 feet long. It has a skinny window, about 3 feet long and 3 inches wide, a toilet, a sink and a bed with a mattress. He's allowed to keep five books at a time and to receive magazines and newspapers that he gets in the mail.

After ten months, Burr says he also earned the privilege of having a TV. He can't talk to anyone except by yelling through a big, steel door. And for one hour a day, usually five days a week, he can leave his cell to exercise by himself in a slightly larger cage outside.

He's also allowed three ten-minute phone calls and one two-hour, noncontact visit per week. With advance authorization and after undergoing a security screening, he has been permitted to record an interview in a small private room.

"How are you?" Burr asks. "Quite a process getting in here, huh?"

Burr is seated in a five-point restraint system: A set of handcuffs connects to a set of shackles at his feet. We're separated by a heavy, glass partition. Because it's difficult to hear Burr through the barrier, an interpreter speaks for him in radio version of this story.

"I think they ultimately believed that at some point I was involved in trafficking drugs," he says when asked why he thinks he's in solitary. "I am saying that just from what the guards are telling me, all right?"

Burr was first confined to the Special Management Unit, or SMU, a year and a half ago. He has put in 20 years of a 60-year sentence for murder.

By now he's familiar with how things work inside. He hasn't been violent in prison or had serious disciplinary problems. He has completed one college degree and is working on a second. But why he's still in segregation, he says he does not know.

"I never got caught with any drugs," Burr says. "The person that they say was involved with me never got got caught with any drugs. So it was very vague. There was really no evidence that I've seen that justified me even getting a write-up let alone leaving me in solitary for 17 months."

Burr went went through the prison's grievance process with no success. And once that was exhausted he filed an appeal of the disciplinary board's decision in Superior Court.

Burr is alleging that the Maine DOC has continuously and systematically violated its own procedures, including falsifying a disciplinary report and failing to provide him with necessary forms and paperwork. He is also alleging that his due process rights have been violated and that his confinement in solitary amounts to "cruel and unusual punishment."

"After we filed we got a notice from the attorney general's office saying 'OK, we agree we can't prove that he tried to smuggle in contraband,'" says Eric Mehnert, Douglas Burr's attorney.

Mehnert says the attorney general's office, on behalf of the DOC, agreed to expunge Burr's disciplinary record, restore 20 days of lost good time and give him back the $100 fine he paid. He was so excited he called Burr to give him the good news.

"And he said, 'That's really interesting, I'm still in segregation,'" Mehnert says. "And I scratched my head and said, 'How can this be?' So, I contacted the attorney general's office and they advised me that they now considered him a security risk under a separate rule and therefore they were going to keep him in segregation and they could do so indefinitely."

In a motion filed with the court last April, Assistant Attorney General James Fortin disputed that he ever implied that Burr could be held in the SMU "indefinitely and for no reason." He also challenged the idea that conditions in the SMU amount to "atypical and significant hardship."

Burr is now living in a special section of the SMU — the Administrative Control Unit, or ACU.

"It's basically longtime solitary confinement indefinitely," Burr says. "It's 15 people that are housed in this unit and they're supposed to be the 'worst of the worst' in the Maine State Prison. Twelve of the 15 inmates are down there for serious, serious violent offenses either on guards or other inmates."

It remains unclear why Burr is considered a threat to the safety and security of the facility. Joseph Jackson, a former inmate who represented Burr in his grievance process and who now works with the Maine Prisoner Advocacy Coalition, says the specific rule involved, Rule 20.1, does not allow for transparency or for the prisoner to hear the evidence against him or to put on any kind of defense before a disciplinary board.

"When they apply this rule to a prisoner, they don't have to have a D-board [disciplinary board] or anything like that," he says. "There's no finding of guilt. They can just apply it to you and hold you."

But Jackson says it makes no sense in Burr's case, given that the attorney general expunged his disciplinary record in the first place.

"If you expunged his record, what did you use to make this decision that he was a threat to the safety and security of this facility?" Jackson says. "And for me, I think it's a way of circumventing the disciplinary policy."

"The bottom line is to get into the Administrative Controls Unit you have to work really hard." says Deputy Corrections Commissioner Rodney Bouffard, a former warden of the Maine State Prison.

Bouffard declined to talk about Burr's case because of the pending court challenge. But he says, in general, the decision to place an inmate in the ACU is carefully considered at multiple levels beginning with prison staff.

"That process involves a recommendation from a team here locally, a recommendation from the warden," he says. "Central office would review the situation, review the inmate, review the inmate's history and then make a recommendation that he go into the Administrative Controls Unit or not."

Bouffard says making the wrong call could wind up getting a guard or another inmate killed.

Burr says he understands that there are a small number of prisoners who need to be segregated from general population, but only for a limited amount of time. And he says the effects of solitary confinement extend beyond the prison's walls to members of his family.

For reasons that remain unclear, Burr's wife has been prevented from visiting with him for a year and a half. His mother, Lucille, who asked that we not use her last name, is using her retirement to pay for his appeal. And she says she loses sleep worrying about his situation.

"It's very hard on me to think of my child suffering and not knowing when it's going to come to an end ,and what they're going to do about this, and how often it happens, and it happens to other people in there," she says. "We never get answers and the DOC thinks they can do whatever they want to whomever they want and not be held accountable for their actions."

Meanwhile, Burr says he struggles not to lose hope on the ACU.

"I'm a very positive person and I went down there like that," he says. "But it changed me a little bit because everything around you is negative. You have people self-abusing and then you have people down there throwing feces and urine so the whole environment is toxic. And the hardest part is not knowing what I need to do to get out of here."

Burr says he has completed several programs recommended by the prison as a way to work his way back to general population. One was called Commitment to Change. But Burr says there is no clear path to follow to demonstrate that you're not a threat.

His status is only reviewed every six months. And at his latest review he says he was told that he needed more time.