When artist Titi de Baccarat first saw someone kneeling as a cultural gesture in the United States, he was both confused and captivated. He watched a man get down on one knee, open a small box, and ask a woman to marry him - a tradition that people in his home country of Gabon did not practice.

Several years later he watched a police officer kneel on the neck of George Floyd, killing him, and sparking protests nationwide.

“I was shocked that the same symbol of love, the same powerful symbol that American people use to build family, to express love, for getting married… the same gesture, somebody uses it to take the life of somebody else,” de Baccarat says.

After Floyd’s death, de Baccarat took to the streets to protest for the first time in his life and witnessed kneeling as a form of activism. De Baccarat moved to Portland, Maine in 2015 as an asylum seeker, and has since been active in the Portland arts community. Inspired by the symbolic power of kneeling in these varied contexts, he began asking people around him what it meant to them. The answers he got led him to start The Kneeling Art Photography Project. The project "aims to promote humanist and social action in the communities of Maine as a response to the local problems of racism and injustices," according to the website.

He recruited nine other Maine photographers, who together have taken over 100 photos of Mainers kneeling. Rose Barboza, founder and co-director of Black Owned Maine, is one of the photographers. She grew up in Lewiston, and says the project is important to show the diversity that exists across the state.

“It's showing the vastness of Maine, because oftentimes Maine is represented like, ‘Oh, it's 94% white, you know, we don't talk about the other 6%, it's such a small number.’ And I think it's really important for projects like this, and for the organization that I run, to talk about the diversity that does exist here. We don't just brush it off,” Barboza says.

Barboza says the Kneeling Art Photography Project also highlights the importance of recognizing de Baccarat’s and other immigrants’ entry points to conversations about racial justice in the Untied States.

“America is built on immigrants and immigrants built this country,” Barboza says. “I think it's really important to recognize that just because you're not born here doesn't mean that your experience is not valid. Titi is creating art based off of what he's seeing and experiencing, and I think it's awesome that he's able to break down a lot of those walls.”

De Baccarat says many people assume that the project started with Colin Kaepernick, the former National Football League quarterback who first took a knee during the national anthem before a game in 2016 and started a nationwide conversation about racial injustice. But de Baccarat says he didn’t know about Kaepernick, or the context around taking a knee as an American protest form, until he saw it firsthand last summer.

For photographer Ann Tracy, the project has become a way to show solidarity with communities of color. Tracy grew up in Maine, then lived in other parts of the country for many years before returning to the state in 2011. When she moved back, she says she was delighted to learn about all of the immigrant communities who have made a home in Maine.

“I think that was the beginning of my awareness of why this kind of a project is needed, to show people a positive approach of all races and religions working together,” Tracy says. “As artists, no matter what kind of art form we deal with, everything we do is a reflection of who we are in the society we live in. I think if we can show each other things that we have not seen in a particular light before, that can be helpful for us to become fully attuned human beings.”

And project photographer John Ripton says he believes it is important to speak up about institutionalized racism as a white person. Ripton grew up in a small town in central Maine, where he says he saw virtually no ethnic or racial diversity, nor any public discussions about it.

“When you do a project like this, I think it does, in fact, move people from one position to another. It facilitates your recognition, or sometimes even confronts you with, ideas and a reality that you might not see on a daily basis,” Ripton says.

Accompanying each photograph in the project is a statement written by the model about why they choose to take a knee.

“I think that no matter what your political beliefs, you could find a paragraph or a model in that room that you resonate with, [because] the statements are so vastly different,” Barboza says.

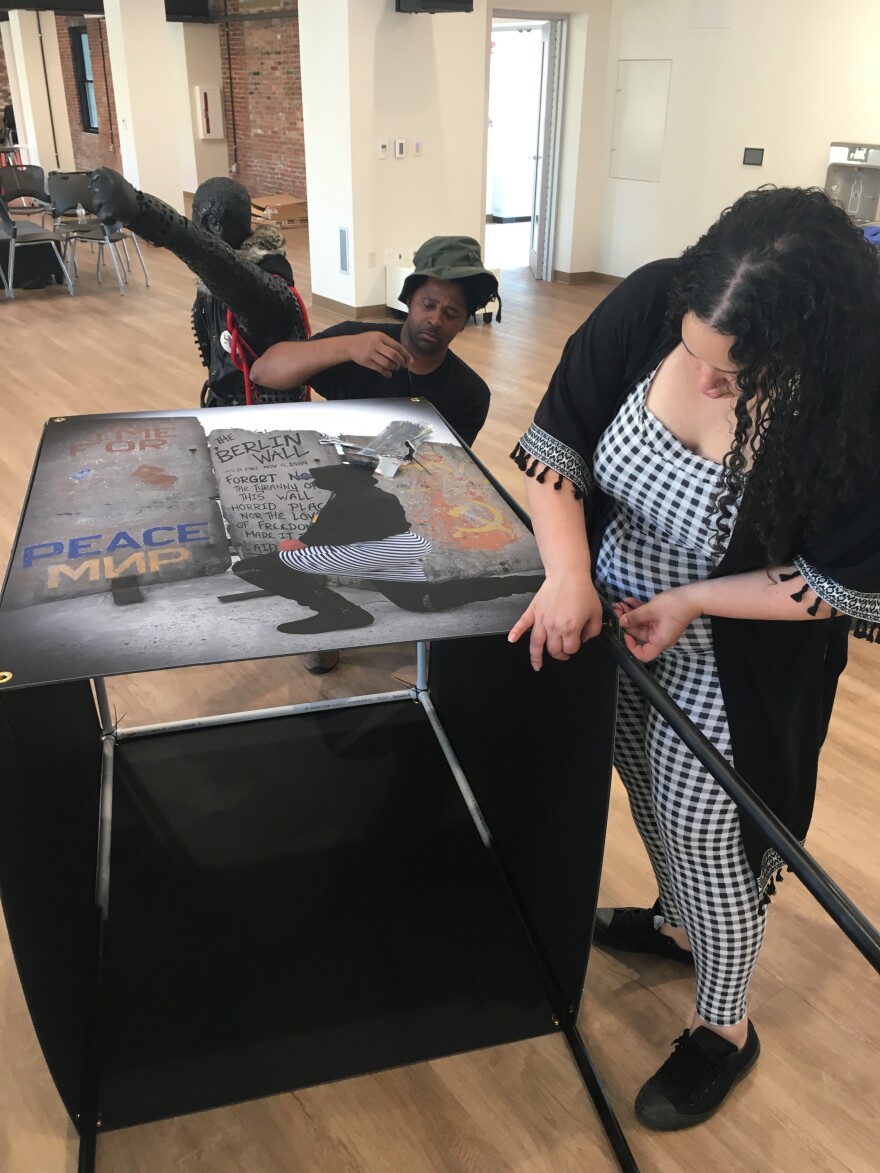

The project has already exhibited at two locations in Portland and de Baccarat and Barboza are setting up the third exhibition at the Arts Collective at 18 Main Street in Waterville this week. On July 9, there will be a special exhibition at Railroad Square Cinema on the opening night of the Maine International Film Festival. The Kneeling Art Photography Project is partnering with LumenARRT!, a collective of video artists, to create an installation that will feature photos from the project. The gallery exhibition will be up for the duration of the festival.

So far, photographers say community response has been powerful. When activist and community organizer Tori Lyn saw the exhibit in Portland, it moved her to tears.

“I wasn't expecting to have that level of emotion, but just seeing all of these different humans, different walks of life, and different experiences of kneeling and saying, ‘this is what this means to me,’ whether it's standing in solidarity with Black Lives Matter, and with the black men and women that have been murdered and harmed over the years, or whether it was their own, personal story of growing up as someone that was underrepresented or marginalized,” Lyn says. “It was powerful to walk around and see all of the different types of experiences coming together for one collective cause.”

Lyn is a special projects coordinator for the Greater Portland Council of Governments, focused on racial equity and economic development.

“I think that there's a common misconception of what activism really is and what it entails,” Lyn says. “Every single person has a level of activism that they either do or don't [recognize], and that they're very, very capable of doing. I think art and photography is a great example of that.”

The exhibition will travel to Orono in September for another show and community workshop, and de Baccarat says he’s already received other invitations to come to Augusta and Kittery. And De Baccarat says a possible book, “Taking a Knee For Change,” is in the works.

Barboza hopes the project will inspire Mainers to take the next step to advance racial justice.

“Obviously over the last year, there's been this this racial social justice awakening,” Barboza says. “But for Black people, for people of color, this is always an ongoing thing. So, let's listen to their voices and center those voices to ensure that we're talking to people who are actually living the experiences. And I really hope that this project allows people to really feel connected, to make it human, to make it more relatable.”

Throughout the project, de Baccarat says he has learned so much about what taking a knee can mean for different people, like when he photographed Jeannie Toppi, who had one of her legs amputated.

“She told me, ‘Titi, I want to be part in your project.’ And I was wondering how could she be, because she only has one leg,” de Baccarat recalls.

In her statement, Toppi writes, “I feel kneeling, deeply with in my heart, but physically I must stand, to represent my grandchildren, who are Black and to end racism and to secure social justice for them, and all other minorities that are daily oppressed.”

“From her I learned that kneeling is not only a physical gesture, but you could also kneel from your heart,” de Baccarat says.