Sea level rise is accelerating along Maine's coast. This year, record high water levels have been documented in Bar Harbor, Cutler and Wells. For coastal communities it means threats to buildings and infrastructure, the loss of beaches and intrusion of salt water into private wells. A modest 1.6 foot rise, which is expected by the year 2050, will result in a 15-fold increase in coastal flooding. Some areas of York County are especially vulnerable as storms become more frequent and more intense.

This story is part of our series "Climate Driven: A deep dive into Maine's response, one county at a time."

For decades, Camp Ellis in Saco has been the poster child for the destructive power of rising seas which have destroyed three dozen homes and washed away several streets.

Coastal damage to the once thriving fishing hamlet has been compounded by the construction of a 150-year-old jetty that altered wave action and carved out chunks of the shoreline. But other coastal communities in York County are increasingly feeling the effects of storm surge.

"So this is kind of a picture of what a future low tide would look like with sea level rise," says Peter Slovinsky, a marine geologist with the Maine Geological Survey.

A recent nor'easter on Wells Beach was more of a glancing blow than a knock out punch, but the day after the storm, the surf remains high, part of the beach is under water at low tide and Slovinsky says it illustrates how low-lying homes and roads nearby are vulnerable.

"Standing on the beach looking north right here there are a bunch of hotels that are at risk of coastal storms. So, when you take the coastal storms and you amplify them by sea level rise, there are going to be some significant impacts to those as well," Slovinsky says.

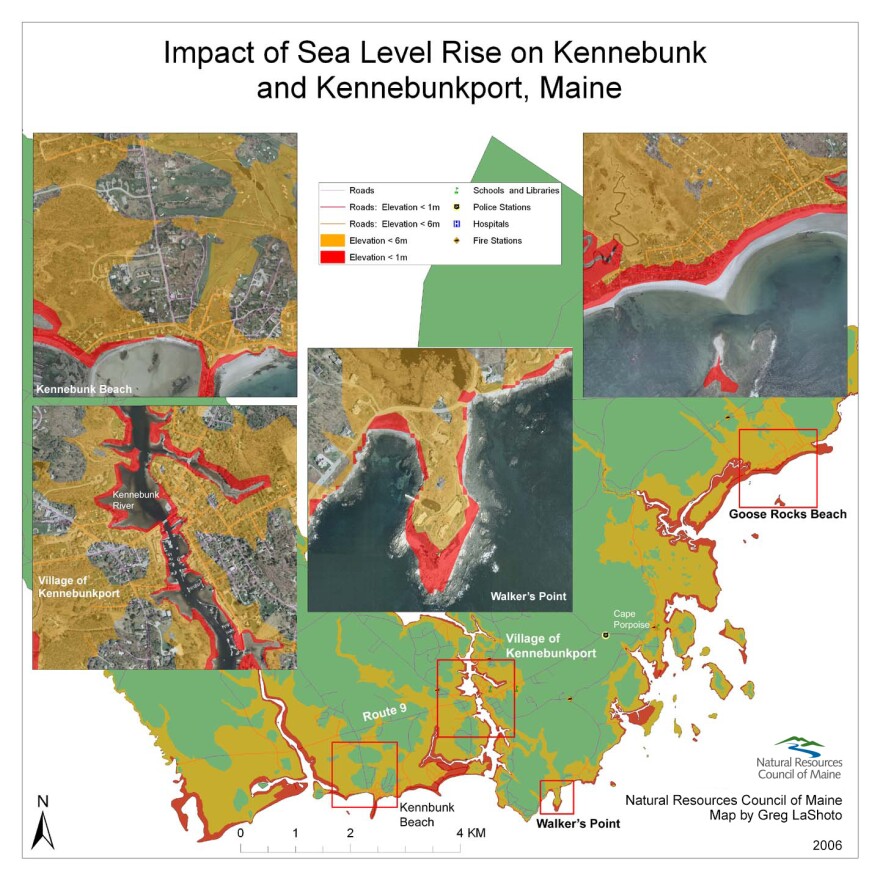

A recent report for the Southern Maine Planning and Development Commission suggests that the more than 3,500 parcels in the towns of Wells, Kennebunk and York are at risk of flooding from an expected 1.6 foot increase in sea level rise over the next 30 years. The combined property value of those parcels is more than $645 million. Larissa Crockett is the town manager of Wells where more than 1,000 parcels are under threat.

"We do have some neighborhoods that are very much at sea level," Crockett says. "We're gonna need to work with those neighborhoods to figure out how to prepare them for the next 50 years."

Crockett says sea level rise is being discussed as part of the town's comprehensive plan. But one of the challenges for municipalities is coming up with the money and the will to finance climate adaptation. Many are heavily dependent on tax revenue from beachfront properties and development which is expected to decline in value over time. For now, Crockett says, just the opposite is happening. Property values remain strong because the town's year-round population of 12,000 continues to grow.

Up the road from Wells, in the town of Kennebunk, homeowner Bill DeSaulnier is showing Captain Barry Jones of the local fire department his basement which flooded after the nor'easter

"I suspect this is the lowest section since the water, in a regular rain storm, it sort of accumulates to your left there, in that area," DeSaulnier says, pointing.

The water table is so high that when it rains, DeSaulnier is forced to pump his basement out. But this time is different, he says, worse than usual. The two-story house sits on a dirt road one street back from the beach where DeSaulnier has been coming since childhood. He says he'll do what he can to keep it standing.

"Overall, I feel like it's my duty to sort of keep up, to the best of my ability, this house. At some point it will probably will be sold, but I hope it continues on as a place of enormous joy for the family and for me. It always was and continues to be," DeSaulnier says.

Near York Beach, Beth and Bob Harrington also plan to stay put and make their small cottage as impervious as possible to the effects of climate change so they can leave it to their daughters.

"I think that we will try to hang onto it and hope for positive change globally. They predict that we'll be under water but it's so beautiful that I can see trying to hang on and enjoying it because it is a special place," Beth Harrington says.

The very thing that makes York special — its beaches, quaint neighborhoods and shops — could see big changes over the next few decades. That modest 1.6 increase in sea level rise? According to the state's Climate Action Plan, it could submerge many of Maine's sand dunes and reduce dry beaches by nearly 45%.

The scale of these impacts can be overwhelming for communities, so the Southern Maine Planning Commission is working with ten municipalities, local land trusts, conservation organizations and federal and state partners on a coastal resilience plan for the region.

"I think it comes down to having community conversations about what people want their communities to look like under future scenarios and not just sea level rise but climate change in general," says Abbie Sherwin, the coastal resilience coordinator.

Sherwin says the plan could include strategies for reducing flooding around the most vulnerable roads and properties, restoring dunes and conserving land to accommodate rising water. Taking action will be key, although Slovinsky says there are only so many things that can be done.

"There's really maybe three, maybe four responses," he says. "The first is you don't build in at-risk areas, which we've already done."

The second, he says, is to protect with a sea wall, for example. Third is to adapt and build higher. And fourth is to simply retreat.

"And there are areas where we're probably going to say the economic impact of moving back or retreating doesn't make sense, we're going to try to protect as long as we can. And there are other areas where the impacts are going to be felt sooner and they're going to be more dramatic, where retreat is going to have to be on the table," Slovinksy says.

Much of the response will depend on resources, on the frequency and severity of storms and on how fast and how high the sea level gets. The Maine Climate Council, on which Slovinsky serves, is recommending that municipalities commit to manage for about 1.5 feet by 2050 and nearly four feet by 2100, but to also prepare for scenarios in which those estimates are doubled.