Melissa Sweet grew up in New Jersey, but when she first came to Maine in the 1970s, she fell in love.

“I came to Maine out of college for a summer job in Acadia at the Jordan Pond House,” Sweet says. “We fell in love with being at Acadia for the summer. I went back and forth for a little while to Boston, but then ended up here for good in the 1990s.”

Sweet says the Maine landscape always works its way into her illustrations.

“I think pretty much any picture book that you pick up of mine, there’s some sort of Maine landscape having worked its way in,” she says. “There’re books with pretty much the view of Casco Bay, all the small islands and evergreen trees. And of course doing the book on E.B. White, it was just a chance to have it all there: the sunsets, the sunrises, the water on the lake, all the boats, his farm. I think, especially for me, it’s about color.”

Sweet has made a career as a highly regarded children's book artist and author. She has won the coveted Randolph Caldecott Medal, twice, as well as the Robert F. Sibert Informational Book Medal; written several bestselling books; and will be a recipient of a 2019 Carle Honor for exceptional contributions to childrenís literature.

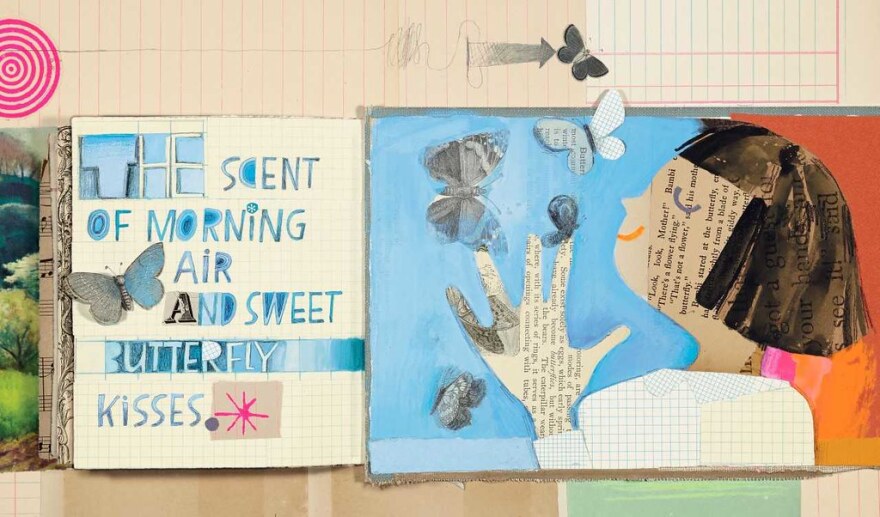

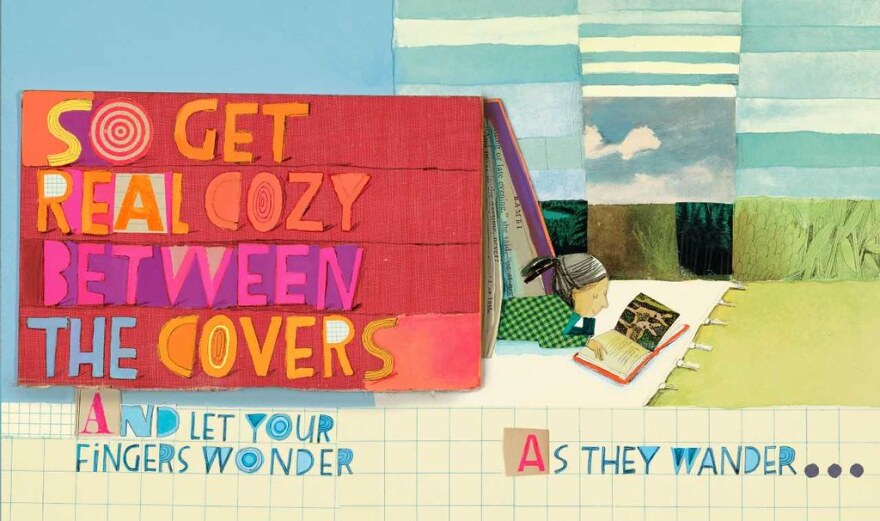

Her next book, due out in June, is a collaboration with Kwame Alexander, called How To Read A Book.

Somewhat unusually for a children's book author, Sweet’s work, both on the books she writes and those by other writers that she illustrates, tends strongly toward nonfiction. In addition to her biography of E.B. White, she has worked on picture book biographies of poet William Carlos Williams, Peter Mark Roget of thesaurus fame, James Audubon, and Tony Sarg, the puppeteer who invented the balloons used in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade.

Her work also includes illustrations in a book of famous inventions by women, and the story of Clara Lemlich, a young Ukrainian immigrant who led the Triangle Shirtwaist Makers’ strike in 1909.

A Unique Style And Process

One thing that is immediately noticeable about Sweet’s work is her detailed, multi-media collages. She says she has always made collages, starting with Colorforms as a kid.

Sweet started as an illustrator with watercolor, ink and pencil, and then “a number of years ago, I began collecting vintage notebooks, ledger books, ephemera and even old library books slated for the landfill as a starting point for my paintings.”

She liked the feel of the old materials, and used them more and more as time went on. These days, she says, she decides which materials to use starting with the story.

“Some books are best simply painted, but often using collage makes a subject become dimensional,” says Sweet. “I gather papers, found objects, do research and look at primary and secondary sources.”

Then Sweet makes a “dummy” or a mockup of the book before she starts building the art. For example, when she was working on Balloons Over Broadway, Sweet built puppets and toys out of old blocks, fabric wood and paper mache, to “mimic the feel” of Tony Sargís studio.

The art is then photographed or scanned, and it is lit so it looks as three-dimensional as possible.

Maine’s Artistic Community

Sweet says she has long been inspired by the work of some of Maine’s most iconic children’s authors, like E.B. White and Dahlov Ipcar. And she says Maine has “such a big, rich community” of children’s book authors, illustrators and artists: people like Jamie Hogan, Scott Nash, and Matt Tavares, Katherine Bradford, Meghan Brady, and Mark Wethli.

Every Child Should Find Themselves In a Book

Children’s writers are often asked why they write for children. Sweet says she does not specifically.

“I don’t distinguish between my work being for children or adults. Maurice Sendak talked about this, but I feel the same way, I would do what I do, pretty much anyway. For me, it’s about crafting a story. So the story might be good perfect for a kindergartner, but it might also be perfect for an adult.”

She says writing books that children can engage with is a “different kind of craft,” though. “In a way it’s harder, because I want to say something succinctly with emotion and clarity, and have it be riveting, all at once.”

This process, she says, involves many edits, to streamline a story so that it is tellable in 32 pages.

But while Sweet says she is not writing to children, she does want children to find her books, or any books in which they see themselves.

“Every child entering a library, entering school, is going to pick a different book. It’s imperative for them to find their book.”

She says that not every kid is going to be attracted to the most popular or classic children’s books.

“It could be the quirkiest book on the planet, that maybe didn’t have a big market, and that kid, they see themselves in that book," she says. "Every kid needs to see themselves in a children’s book and we need as many as we can publish that are true, and authentic, and speak to a child.”

Originally published April 20, 2019 at 1:41 p.m. ET.

Due to an editorial error, an original version of this post mis-credited certain images. They have been updated.