It's Nov. 11 — Veterans Day. Originally marking the end of World War I, Veterans Day has come to signify the lives and sacrifices of the men and women who have served in the armed forces.

In honor of Veterans Day, Maine Public's Jennifer Mitchell looks at some of the issues facing today's veterans organizations, while many are still coping with the losses of more than a century of wars.

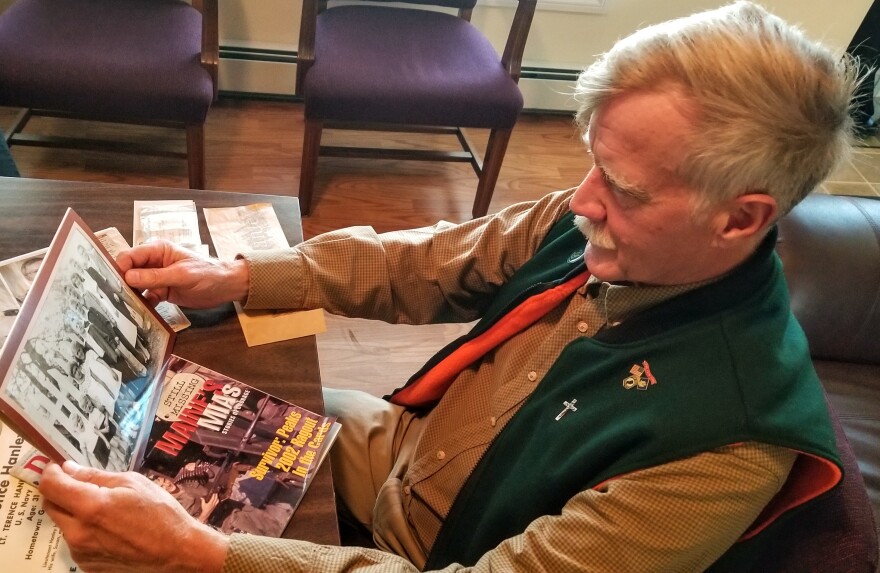

We begin with a personal memory from state Rep. Jeff Hanley, who serves in Maine House District 87.

Terry's little brother

"I'm Jeff Hanley, I live in Pittston, Maine. I grew up in Gardiner. I'm 70 years old.

"Lt. Terence Hanley was my older brother. He was like my second father, the big brother you really want and he showed me camping and fishing and hunting and canoeing and a wonderful guy. I don't think that guy ever got in trouble. Ever, to my knowledge. Not like some of the Hanley boys. Terry was in the ROTC program, St. Anselm's. We were not well off, and they were in no position to help him with school. Terry, I think took on the Navy role simply to help him get through school. And then he was going to do his time with the military and come home and start his own existence. As far as what he wanted to do, I'm guessing from the stuff I saw him do he was going to head into an engineering world. And that would be where he would be.

"In a reconnaissance mission over North Vietnam, his plane was shot down on New Year's Day of 1968. And that was the last we've ever seen or heard of him. So it's been, what, 53 years? You don't remember every moment of every day, but I remember that very clearly. It was cold. I remember my parents were at the house with Father McVicker, the Catholic priest from St. Joseph's. And he was accompanying them, and I knew the second he walked through the door, something was dramatically wrong. And he was only, I think, a couple of months into marriage. And his only son was born while he was still in the early stages of being missing, and so his wife was a widow before she was a mother.

"Terry's wife even went to Paris and handcuffed herself to the gates of the embassy, the Vietnamese embassy over there. It was a big international scandal. You don't want to have your husband declared dead. But what do you do with yourself and your son? How many years do you wait in exile? And she finally had to make that decision, and then remarried after. It always affected her, all her life. She never had any other children. Never talked to me. We just didn't. We don't. We still don't. A word here and there now and then.

"I don't know why, what the psychology is behind a family not discussing it anymore. I suppose rather than keep opening a wound up, because there's no healing the wound, it's always open, it never gets healed. That would be — again, I can't even analyze myself. It's painful. And veterans, you know, they're part of the three-legged stool, I guess. You need them — you wish you didn't, actually, it'd be nice not to have veterans. I would ask people to remember that.

"You get up on Nov. 11, and you got a day off. You're gonna be able to drive anywhere you want, walk anywhere, sleep as late as you want. People need to know — that day off is purchased with blood."

'We would never forget'

Debra Couture is a 24-year veteran of the Navy and the fourth female commander of the Maine American Legion since the organization started more than 100 years ago. She's visiting a wall off busy Route 100 in Winslow, bearing the names of 419 Mainers who are still missing and 59 who are listed as prisoners of war.

Like the Hanley family, Couture's family also didn't talk about her two uncles who were killed in WWII. One of them died and was brought home. The other died and remains missing.

"So he's right here — Lawrence Pierce," she says, pointing out his brick.

Couture says it was not uncommon for 20th century military families to just bury their grief — and maybe hope for answers in the next life. But today, she says one of the most important services the American Legion can provide is to address grief, talk honestly about PTSD and help families cope.

"Just making sure that you can put your arms around them and say, 'Look, whatever you experienced, I understand.' And we need you to be a part of our organization so that we can help you — and you can help others," she says.

But membership in organizations like the American Legion and the VFW have been in decline even before the COVID 19 pandemic, which has had further impacts.

Nationwide, the Legion has lost about a million members over the last 20 years. In 2017, South Portland's VFW hall closed due to lack of funds. Brewer's VFW post, also out of funds, closed its hall and merged its members with Bangor's. Such closures are especially notable in Maine's small, rural communities.

"We're still here. We're trying. If it wasn't for the fact that this is such a caring community, we'd probably be closed too," says Navy veteran Mike Majkowski, who commands Legion Post 80 in Millinocket.

He's worried his post will go the way of the VFW hall just up the road, which is another post that recently shut down. It used to be a bustling place for events and fundraisers, but as veterans from WWII, Korea and Vietnam pass on, Majkowski says younger service members from Iraq and Afghanistan just aren't joining the organizations — but he thinks he understands at least part of the reason why.

"You get a few. But when they come home, the last thing they want is anything that's military based. I mean, this is just my own personal opinion. When I got out, I didn't want anything to do with the military. Once you're done, you're done," he says.

But Majkowski's feeling about that changed abruptly on July 8, 2010.

"My younger brother was the vet who was killed down to Togus 11 years ago. James Popkowski," he says.

James Popkowski, 37, was a Marine Corps vet who was dying from a rare form of cancer. He suffered an apparent mental health crisis and arrived outside the Togus VA Clinic in Augusta carrying a gun.

Majkowski says the incident left him confused, grief stricken and angry. He realized then that veterans, himself included, needed a lot more support from the VA system — and from other veterans.

"I need to go someplace. I need to get with other vets. The Riders, they got me back involved, you know, doing what they did for my family. I wanted to do something in return," he says.

The American Legion Riders escorted the body of 2nd Lt. Ernest Vienneau to his final resting place in Millinocket last month, after he'd been missing in action for decades. It was a very unusual event for them, and for the Defense POW-MIA Accounting Agency, whose job it is to try and repatriate remains.

Kelly McKeague, who directs the agency, says there are still almost 82,000 service members missing, and only 38,000 are potentially recoverable. But he says, looking at the numbers, he's hopeful that 21st century military families won't have to endure the same decadeslong recovery missions their forebears have.

"Seventy-two thousand are from World War II, 7,500 from Korea, 1,500 from Vietnam," he says. "Twenty years of combat in Afghanistan? Not a single MIA."

It should be noted that thousands of other soldiers are still missing from WWI, but no efforts are being made to recover their bodies — too much time has passed to make it a priority. So having a service member returned after the clock has been ticking down for 77 years? That was special for Millinocket.

"It's a miracle. I get goosebumps just thinking about," says American Legion Riders' Rick Cyr.

The day before Vienneau's long-delayed funeral, Cyr and Shawn Boutaugh were among those volunteering to make a giant vat of spaghetti for Vienneau's friends and family. In their mid 40s now, Cyr says he and Boutaugh are the babies of the post riders — and that's part of the problem. Younger people have different priorities, he says. They're still raising families and trying hold down jobs and just "do life."

They say until small, rural towns like Millinocket find a way to boom again, it's going to be a rough road ahead for military service organizations. They say their generation has had to move for work opportunities, with nothing to do in town. Boutaugh works in New Hampshire now, and only comes home on weekends.

Couture acknowledges that members are fewer now, and she gets the same few people volunteering for everything at her local post, but she feels organizations like hers still have a role to play. She says many young veterans don't have cohesive family and community supports, and veterans both young and old have no idea what benefits or health care options they're entitled to, or how to navigate the VA system. She's also hoping that veterans' groups can develop more civic education programs for students and reach out more to the post-9/11 generation to find out what their needs are.

But she says they can't forget about the 82,000 families nationwide whose loved ones probably won't ever make it home.

"Every post has a POW-MIA table, with an inverted glass and a place setting there," she says, "to always remember those who haven't returned. It's brought up at every single meeting that we have. We would never forget."

When a service member's remains are found and brought home, a gold star is placed next to their name on the memorial. So far in Maine, stars have been placed next to the name of Alberic Blanchette, a 19-year-old Marine from Caribou who was killed while serving in 1943. His remains were returned in 2017.

Also recently getting his star was 25-year-old pilot Vienneau of Millinocket. The remaining 478 are still waiting for theirs.