The commissioner of Maine’s Department of Marine Resources has kicked off three days of meetings with Maine lobstermen to present details of the agency’s latest proposal for meeting a federal mandate to reduce the risk to endangered North Atlantic right whales from entanglement in their gear.

Lobstermen continue to be skeptical that their trap rope is injuring or killing whales, but there is a grudging willingness to give the state’s proposals a try.

DMR Commissioner Patrick Keliher started with a warning for the dozens of fishermen who showed up in Ellsworth last night. He told them they are up against a legal reality that has proven its power in other showdowns between the interests of an industry and an imperiled species — the federal Endangered Species Act.

“That Endangered Species Act has tremendous teeth,” he says. “It’s a big hammer when they swing it.”

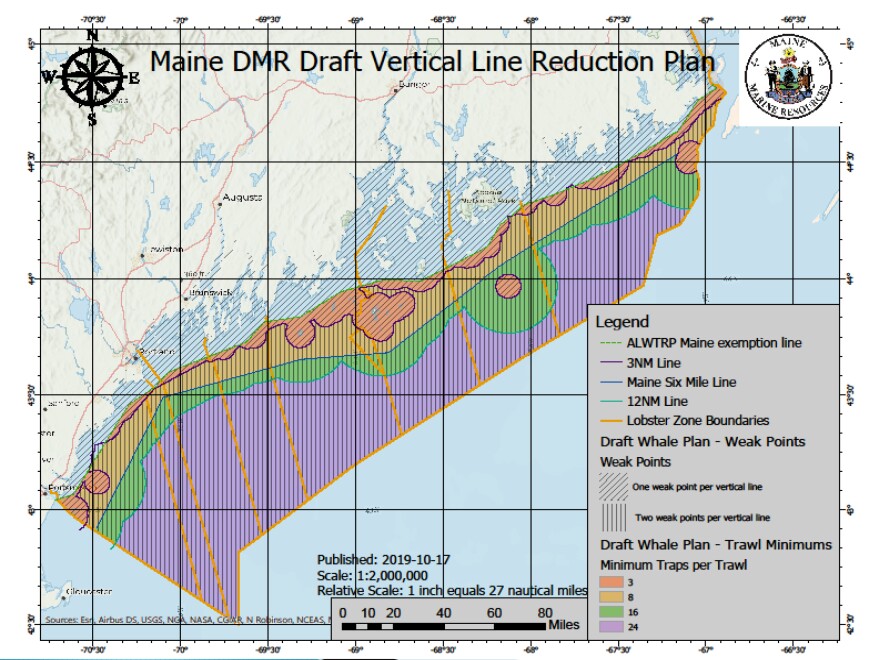

In an effort to meet the ESA’s requirements, an earlier proposal initially endorsed by the state could result in large-scale removal of rope from the water, significant increases in the number of traps fished per line and potential reductions in the number of overall traps fished. But the state’s latest plan would exempt from the rope reductions boats that fish within a zone that extends roughly three miles from shore. That’s most of the state’s lobster fleet.

Keliher says that’s where the state’s risk analysis shows the likelihood of harm to the whales is lowest. And the result, he says, would be that instead of taking half of their 5.5 million rope lines out of the water, Maine’s fleet would need to reduce that number by only a quarter.

“That is a major change from what we brought forward in June. And then we remove closures and trap reductions from the conversation,” he says.

Fishermen peppered Keliher with questions on the details. Many were concerned about proposed requirements that they incorporate “weak links” into their rope lines that would allow whales that encounter them to break through.

Jack Merrill, a lobsterman from Little Cranberry Island, says that offshore fishermen who would also be required to add more traps per line, called “trawling up,” would find that unwieldy and even dangerous.

“I know where I fish between 3 and 12 miles, I would say there’s 20-30 guys that fish there now. If this goes into effect, at least half of those guys are going to move inside. Because they are not geared up, their boats aren’t big enough. It may be their age, one crew, they’re not geared up to trawl up. So you’ve changed the dynamics of the fishery completely, and put a lot of people in a really bad spot,” he says.

Kristan Porter, a Cutler lobsterman, agrees that the changes in gear configurations would be difficult to contend with and would result in more traps lost when ropes get tangled up and break.

“It sucks,” he says. “I fish in some of the harshest conditions. But I’m going to try it.”

Porter is president of the Maine Lobstermen’s Association. He emphasized that he was speaking only for himself, because the MLA board has yet to meet and decide a position on the new proposals.

“The reason I’m going to try it is we’re getting a pretty good chunk of risk-reduction by going this route, and I’d rather give this a shot over the next year if we can make it work. I know you’re going to have tangles. People are going to have part-offs with tangles, it’s just going to happen. But what’s the alternative?” he says.

Some lobstermen wondered whether the state’s marine patrol would enforce a federal mandate against lobstermen who defied it.

“Am I going to see a state of Maine boat coming over to tell me to go to shore or put me in cuffs because I’m out there hauling?” says Birch Harbor fisherman John Renwick.

Renwick put Keliher on the spot, asking what he would do if, in response to a federal lawsuit filed by conservationists last year, a judge shut down the Maine lobster fishery. Keliher says the state would fight back in court.

“But at the end of the day we have to enforce the law of the land, whatever that law is going to be, even if we disagree up until the point that it is finally decided,” Keliher says.

“That being the case, I’ll volunteer to be the first one you can come and get,” Renwick says.

Keliher continues his efforts to cultivate the lobster industry’s support for his answer to the federal requirement to reduce risk for the endangered whales this afternoon in Waldoboro, and Wednesday in South Portland.

Originally published Nov. 5, 2019 at 6:23 a.m. ET.