Question 2 asks Maine voters: “Do you want to ban foreign governments and entities that they own, control, or influence from making campaign contributions or financing communications for or against candidates or ballot questions?”

If voters approve Question 2 in November, Maine will join an emerging trend of states and localities seeking to curb foreign electioneering in campaigns while also seeking to overhaul a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision that has unleashed a wave of unfettered corporate spending on elections.

While available polling suggests the concepts of the proposal enjoy strong public support, critics warn that Question 2 may be unconstitutional and run counter to the same the 2010 Citizens United ruling that the legislation ultimately seeks to overturn. Meanwhile, state press and broadcast associations have raised objections to a provision in the proposed law that would require news outlets to determine whether a prospective campaign advertisement is being purchased by a foreign-government owned company or entity, or face financial penalties.

Overall, Question 2 aims to close a loophole in state law that currently allows companies and organizations owned by foreign governments to spend money to influence voters on state referendums. In doing so, it taps two populist sentiments about U.S. elections: first, that money plays an outsize role in determining outcomes, and second, that entities controlled by foreign governments should not be allowed to influence voters.

The origins of Question 2

Question 2 is an outgrowth of attempts to scuttle a $1 billion electricity project in western Maine.

@mainepublic If voters approve Question 2 in November, Maine will join an emerging trend of states and localities seeking to curb foreign electioneering in campaigns while also seeking to overhaul a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision that has unleashed a wave of unfettered corporate spending on elections. 🗓️ Election Day is Nov. 7! #mepolitics #mainenews #vote #election2023 #electioneering #citizensunited ♬ original sound - Maine Public

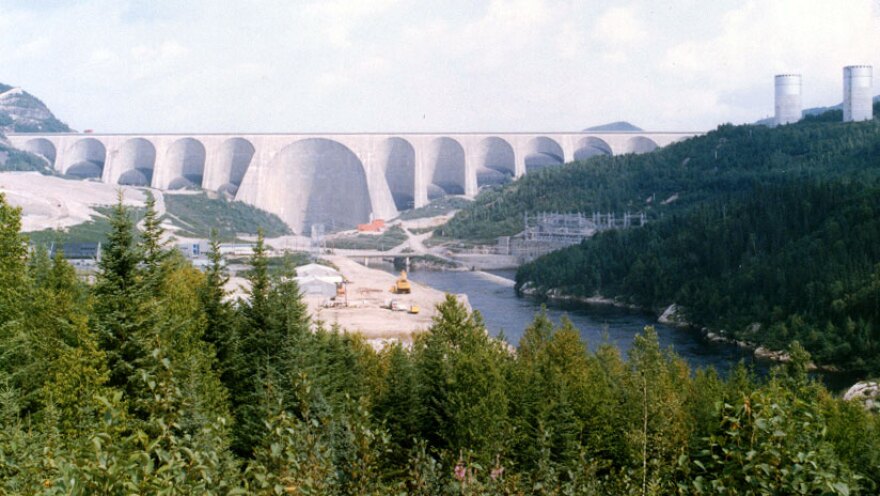

In 2019, opponents of the transmission corridor began organizing a referendum campaign that would halt the project. As opponents gathered signatures to put the issue on the ballot, Hydro-Quebec, the electricity supplier for the transmission line, formed a ballot question committee that would spend money on advertising to convince Maine voters that the corridor was in their best interests. The prospective electioneering effort by Hydro-Quebec raised a legal question first reported by Maine Public: Can a company wholly owned by the Quebec government spend money to influence a Maine election?

The answer was yes. Maine election law and the Federal Election Campaign Act explicitly prohibit foreign nationals from contributing to, or spending on behalf of, candidate campaigns. However, both state and federal law are silent on the issue of foreign electioneering in state referendums.

Opponents of the corridor, backed by campaign finance reformers, attempted to close the loophole in 2021, potentially sidelining Hydro-Quebec from the upcoming referendum campaign. Business groups rallied to Hydro-Quebec’s cause, arguing that a proposal that would have barred the government-owned utility from electioneering was unfair and possibly unconstitutional. Those arguments were persuasive to Democratic Gov. Janet Mills, who vetoed the bill after it cleared the House and Senate. Hydro-Quebec went on to spend $22.3 million on election communications during the corridor referendum.

The veto inspired the creation of the group Protect Maine Elections, which vowed to put the issue of foreign electioneering before voters and did so this year. Supporters also attempted to convince state lawmakers this year to enact the initiative and bypass the referendum, but Mills vetoed that bill too, and once again, supporters of the ban couldn’t muster the votes to override her.

What does Question 2 do?

Question 2 has several important provisions, but its main objective is to make electioneering in state, county or municipal referendum illegal for companies or entities owned or controlled by a foreign government.

If the legislation had been law in 2021, Hydro-Quebec would not have been allowed to advertise against the anti-corridor referendum. (As it turns out, Canada prohibits candidate and referendum contributions from noncitizens.)

Similarly, if the legislation had been law and in effect this year, it would have sidelined Maine’s second largest electricity provider, Versant Power, from spending against Question 3, which would replace Versant and Central Maine Power with a statewide utility run by an elected board.

That’s because ENMAX is a corporation owned by the city of Calgary, Alberta, a foreign government as defined in the Question 2 legislation. (A political action committee funded by ENMAX has so far amassed $8.4 million and spent $2.5 million against Question 3.)

Question 2 also prohibits schemes that might be used to circumvent the foreign government electioneering ban, while also requiring media outlets — TV, radio, newspapers or internet platforms — to create “diligence policies, procedures and controls that are reasonably designed” to prevent foreign government-purchased election advertising on its platforms. (The Maine Association of Broadcasters, of which Maine Public is a member, is fiercely opposed to this provision, as is the Maine Press Association, which includes many newspapers as members.)

Question 2 also requires the four members of Maine’s congressional delegation to sponsor or co-sponsor an “anti-corruption” resolution in Congress.

According to the proposed law, the congressional resolution would be consistent with a resolution that the Maine Legislature backed in 2013 that called for an amendment to the U.S. Constitution that would undo the Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision.

A key distinction: Foreign owned vs. foreign-government owned

Since the debate began over Question 2 there has been some confusion — and outright conflation — of how the proposed law would affect businesses with foreign owners or foreign investors.

That concern over silencing Maine companies with foreign ownership was part of the governor’s argument against the first iteration of the bill in 2021.

“Entities with direct foreign investment employ thousands of Mainers,” Mills wrote in her veto message. “They include Stratton Lumber, Woodland Pulp and Paper, Backyard Farms, McCain Foods, and Sprague Energy, to name just a few. Legislation that could bar these entities from any form of participation in a referendum is offensive to the democratic process, which depends on a free and unfettered exchange of ideas, information, and opinion.”

However, that proposal, and Question 2, don’t explicitly target foreign owned companies. It targets companies or organizations owned or controlled by foreign governments.

Nevertheless, how the proposed law defines ownership and control by those foreign governments is a key issue.

Versant Power has acknowledged that it would be affected by the electioneering prohibition. But what about Central Maine Power, which is owned by Spain-based Iberdrola, which in turn is partially owned by a sovereign wealth fund controlled by the Qatari government? CMP says it’s unaffected by the proposed ban, but it still lobbied against the bill that would have enacted Question 2 in the legislature this year.

Question 2 defines foreign government ownership and control as “a firm, partnership, corporation, association, organization or other entity” that a foreign government or a foreign government-owned entity “holds, owns, controls or otherwise has direct or indirect beneficial ownership of 5% or more of the total equity, outstanding voting shares,” or “directs, dictates, controls or directly or indirectly participates in the decision-making process with regard to the activities of the firm, partnership, corporation, association, organization or other entity ...”

That definition hasn’t settled the debate over Question 2’s potential impact, however.

The Forest Products Council, which represents an array of timber-based companies and landowners with foreign investors, testified this year that the question’s 5% rule “would be very difficult to follow for businesses (including U.S.-based businesses) that are publicly traded and may have foreign government pension funds as investors at any time.”

Mills cited similar concerns in her veto letter this year, describing it as “so broad that it could theoretically incorporate businesses that are 95% owned and operated by citizens of Maine.”

Supporters of Question 2 sharply dispute those characterizations. Protect Maine Elections chairman, state Sen. Rick Bennett, R-Oxford, says the proposal is narrowly tailored compared to its counterparts in other states and localities, and that its primary aim is to prevent foreign governments from exerting influence on Maine referendum elections through corporate subsidiaries.

Is Question 2 constitutional?

There are two arguments over the constitutionality of Question 2. The first involves the legality of restricting political speech, which includes campaign advertising. The other involves the “due diligence” mandate in Question 2 that requires news outlets to determine whether an advertising communication on their platform is paid for by a foreign-government-owned company or organization.

While supporters and opponents of Question 2 point to several court cases that bolster their respective views, a court case analogous to the restrictions on political speech that Question 2 proposes appears elusive. For that reason, we won’t get into the arguments in detail, but those interested can read supporters’ case here and opponents’ case here.

Nonetheless, if Question 2 passes, its restrictions on political speech might face a legal challenge.

It’s unclear whether Question 2’s due diligence mandate for press outlets awaits a similar fate, but First Amendment concerns are also an issue. The Maine Press Association in July issued a scathing critique of the proposal through its attorney while urging Mills to veto it. The MPA letter framed the requirements as affecting news outlets’ independent control over what they publish and “restrict and burden speech about public issues in Maine by forcing news outlets to create an oppressive, time-consuming, and costly self-censorship regime.”

The Maine Association of Broadcasters also cited First Amendment concerns while saying that the due diligence requirement would place “an almost impossible burden on Maine broadcasters, operating on fast turnaround deadlines for placing advertising and often with a skeleton staff.”

It added, “This law would essentially require broadcast outlets to become detective agencies, tasked with investigating the source of funding for any and all campaigns.”

Aaron McKean, legal counsel for the Campaign Legal Center, countered that the due diligence requirements are not nearly as onerous as news associations have described them. McKean said commercial broadcast outlets are already required to keep a political file that tracks political advertising for each election. He said that the penalty provision in Question 2 isn’t meant to punish broadcasters or news outlets for not discovering that a foreign government entity has gone through great lengths to conceal its funding of an advertisement — a requirement that would require deep knowledge of campaign finance. He described the provision as a reasonable standard designed to “ensure that foreign government entities can’t use news outlets to break the law.”

It's not entirely clear what Question 2's due diligence policies might look like in practice, or how they might be enforced. The legislation suggests enforcement might fall to the Maine Ethics Commission, which regulates state campaign finance laws.

But director Jonathan Wayne says the proposal is ambiguous on that point and that the agency would have to create rules clarifying the standards while also balancing First Amendment protections for the press if Question 2 passes. "The Commission respects the First Amendment and any policy decisions that would have to be made down the road would be consistent with the First Amendment. And I think, in general, we're not looking to regulate broadcasters or news organizations," he said. "That's not what we see as our current role."

Wayne also noted that news organizations are already prohibited from running ads that don’t contain a disclosure saying who paid for them. In theory, he said, the commission could fine news organizations that allow such ads to run.

“But in practice we never do," he said. "We always hold the party whose responsible for the content of the ad to task if they have not included all the right information."

The Citizens United connections

One of the reasons state and national campaign finance reformers support Question 2 is because it seeks to reverse the effects of the Citizens United decision that yielded an explosion in campaign spending by corporations.

The “anti-corruption” provision in Question 2 is an overt attempt to undo Citizens United, but the proposal also has roots to other ambitious initiatives that would blunt the flow of corporate campaign cash even if Congress doesn’t nullify the Supreme Court’s landmark ruling with an amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

Some of those proposals were introduced in the previous legislative session. They didn’t just target electioneering by companies controlled by foreign governments, but also electioneering by corporations with foreign ownership. Lawmakers balked at those proposals, but campaign finance reformers viewed them as a key to blunting the spending unleashed by Citizens United. Minnesota’s legislature recently passed such a law dubbed the Democracy for People Act. In June the Minnesota Chamber of Commerce challenged the constitutionality of the law and some of the same campaign finance reform groups that testified in favor of similar bills in Maine are organizing to defend it in court.

In that context, Question 2 is a more narrow attempt to curb spending on elections by corporations with foreign ownership.

Opponents of the legislation don’t view it that way and have thus framed it as a proposal nearly as sweeping as electioneering bans on foreign-owned companies that Maine lawmakers abandoned in 2021.

Maine's Political Pulse was written this week by chief political correspondent Steve Mistler and State House correspondent Kevin Miller, and produced by digital editor Andrew Catalina. Read past editions or listen to the Political Pulse podcast at mainepublic.org/pulse.