On Monday, Maine Gov. Janet Mills' administration will hold its first summit on addressing the opioid crisis. It will bring together health providers, advocates, police and other first responders as well as people whose lives have been touched by opioid addiction.

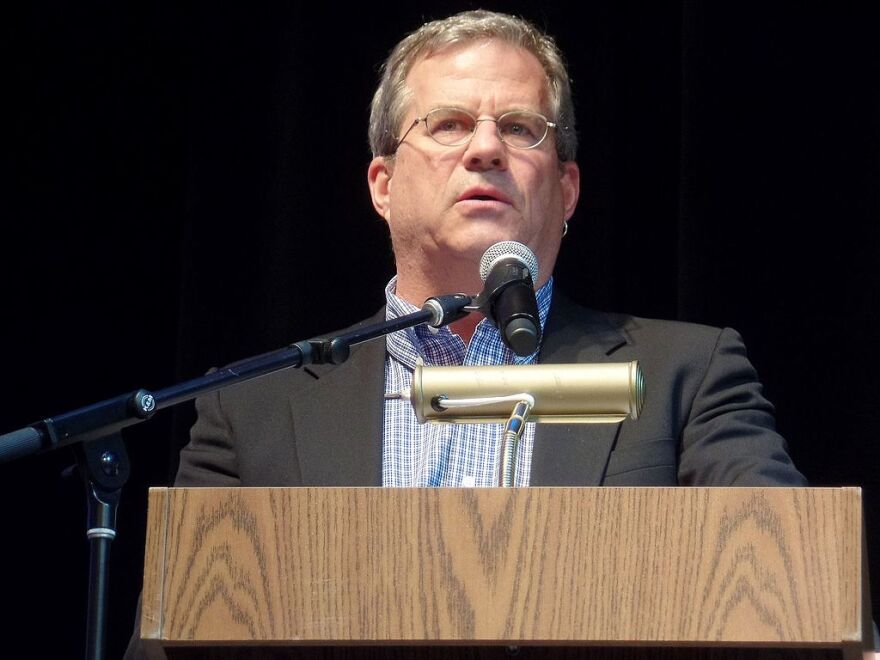

Journalist Sam Quinones will be a keynote speaker at the summit. His 2015 book Dreamland: The True Tale of America's Opiate Epidemic, tells the story of how a combination of legal and illegal drug marketing and changing attitudes toward pain management laid the groundwork for the crisis in America.

He spoke with Nora Flaherty on All Things Considered.

Sam Quinones: We arrived at the point where we are today because of, initially, a push to transform how we treated pain. And, in treating pain, the greater, far more aggressive use of narcotic painkillers for all manner of pain, a variety of ailments in many, many people regardless of their background. So as time went on, people got addicted to these drugs, and a lot of them switched to heroin, not everyone, but a good number switched to heroin, along the way with the pills. And then of course, with heroin as well, we began to see increasing overdoses, people dying. And more recently, we've seen that heroin has been crowded out by the underworld use of a drug called fentanyl, which is another opioid that is synthetic, and that has even further increased the death toll.

Nora Flaherty: Now this book came out in 2015. How have things changed since then?

First of all, the negative: you have, as I said, an expansion of this drug called fentanyl, which is actually a legitimate painkiller used in surgeries a lot. And sometimes in the use of chronic pain in modern medicine. It's been discovered by the underworld as a very, very cheap, therefore enormously profitable, substitute for heroin. It's also extraordinarily potent, and therefore very, very deadly. And that is what has motored the death toll over the last few years, is really fentanyl.

On a positive side, I would say that we are seeing an enormous expansion of awareness. And this whole problem that early on, when I was writing my book, there was a deafening silence surrounding this problem, nobody wanted to talk about it. It was very much like the early days of the AIDS epidemic, everyone wanted to hide it, and so on, you thought it was very difficult to find families who wanted to talk about this in public.

And since the book has come out, I think what's happened is an enormous new awareness. People are feeling the courage to come out of the shadows. Obituaries are telling the truth. You're seeing enormous expansion of lawsuits against drug companies, which was never the case when I was doing the book. And so you're seeing at the same time that the enormous death toll rising, you are also seeing Americans kind of wake up to this problem and begin to work together on it.

You mentioned these lawsuits, and we have just gotten news of another very big settlement. But are the lawsuits changing anything?

I would say that what is happening is just the mere fact of the number of lawsuits is doing a few things. First of all, it's bringing out the full story of a much fuller story than I was able to get being just one freelance writer.

I would say also that, increasingly, drug companies are seeing that they need to be proactive, that they have maybe gotten a little complacent by beating down too many very vulnerable clients and plaintiffs without a lot of power to them. And they thought that they could kind of get away with a lot that I don't think they're now able to get away with. And so you're seeing the companies react a lot of times with far less arrogance, frankly, than they displayed, like in the late 1990s, early 2000s. So these changes are having put the full effect of the lawsuits and the hundreds and hundreds of lawsuits that have piled up. I'm not sure we're going to see that for a while yet.

If I go to the doctor today, and I say I have pain, what can you do for me, what's likely to happen?

If you go to a doctor who actually has a lot of training in pain management, that doctor, I would hope, would would be able to prescribe you a wide array of treatments, opioids being one of them, but only part of the mix. Also physical therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy and exercise and diet and so on and so forth. The problem is, nowadays, that one of the key elements that got us into this, which we still have not addressed, is the fact that too often insurance companies do not reimburse for a whole lot of pain treatments that do not involve opioid painkillers. So it's kind of hit and miss.

And some doctors without a lot of training and pain management have chosen just to shut people down just to stop prescribing or just refuse patients. That's very cruel. It also sends people into the black market looking for their for their pain meds. Chronic pain patients still do not have a wide smorgasbord of treatments from which to choose from and to use all together, one in concert that insurance companies will reimburse for. Some HMOs are doing that, but I think too often you're still finding out that doctors don't have many tools for the patient who comes before them and says “I have chronic pain.”

Sam Quinones is the author of the book “Dreamland: At The True Tale Of America's Opiate Epidemic.” He'll be a keynote speaker at Monday's 2019 Maine Opioid Summit in Augusta.

Ed note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Originally published July 12, 2019 at 4:10 p.m. ET.