It's often reported that the Gulf of Maine's waters are warming faster than 99 percent of the largest saltwater bodies on the planet. But scientists will tell you the trend can be volatile. This year, for instance, surface water temperatures in the Gulf have been their coolest since 2008. That may be providing some relief for some of the Gulf's historic species, but ongoing climate change means that long-term prospects are still uncertain.

Lobsterman Seth Dube fishes 400 traps from his boat, the Alison Nicole, out of Camp Ellis in Saco.

"Off and on most of my life, and my father did it and my grandfather and now me, hopefully my boy," Dube says.

This has been a good decade for Dube and the rest of Maine's lobster fleet, with record catches most years since 2010. But this year, the beginning of the big summer harvest – when lobsters molt, shedding their old hard shells to reveal new, soft shells – was slow. Lobstermen and some scientists associate that with cooler water temperatures earlier this year.

"It's still not all that great. I mean it's all right fishing, but it hasn't been no record breaker that's for sure... Prices stayed up pretty good, stayed up pretty good," says Dube.

Some lobstermen say they have just begun to see some improvement in the harvest this month – reminiscent of what was traditionally called the "school-bus shed," because it comes on just when the academic year begins. That kind of reversion to historic ecosystem timing is being seen elsewhere in the Gulf.

"This is the most normal, the most average year that we've had in a really, really long time," says Andrew Pershing, the chief scientific officer at the Gulf of Marine Research Institute in Portland.

Pershing is the one who first marshaled the data showing that warming in the Gulf was outpacing the rest of the world's oceans.

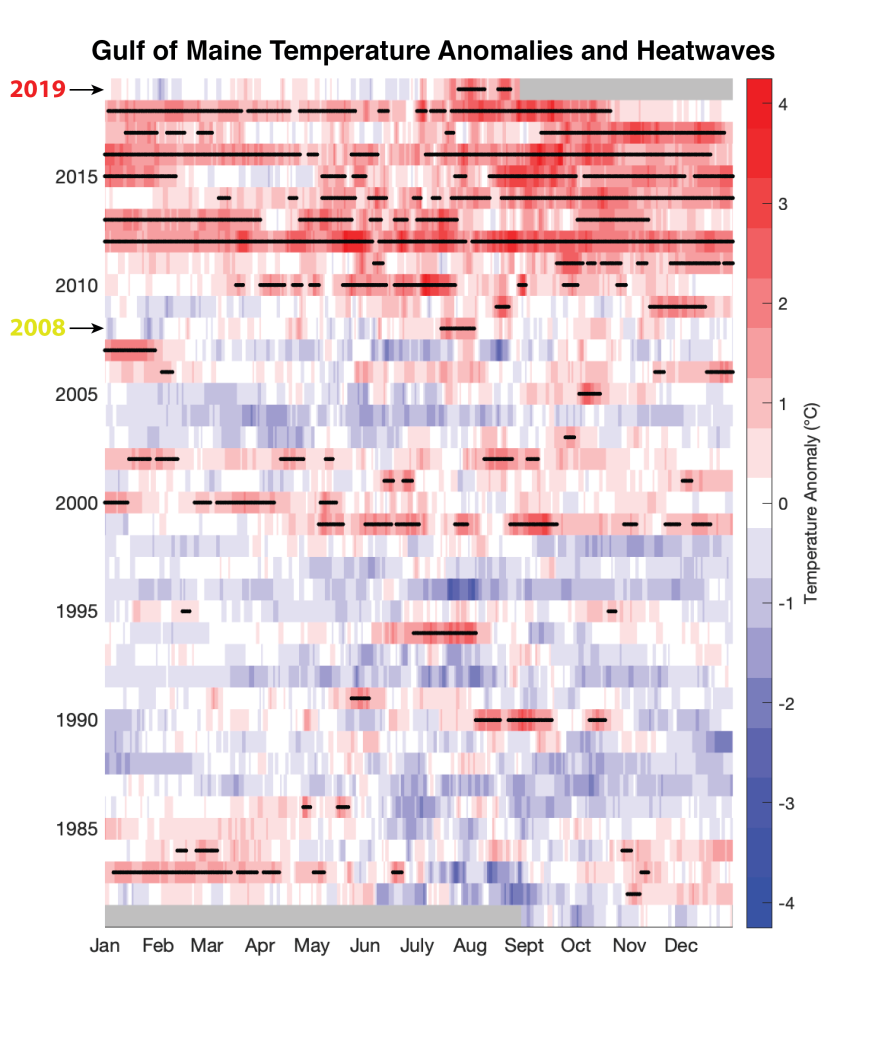

But so far this year, he says, the Gulf's water temperatures are the coolest since 2008.

"The surface temperatures in the ocean have really closely tracked basically the 30-year average conditions, and I think what's telling is that we talk about that as a cold year, when in 2008 and that happened, we would have probably said 'well this is sort of an average to maybe a little-above-average year,'" Pershing says.

It's a contrast to the rest of this decade, particularly 2012, when water temperatures ran almost four degrees Fahrenheit above the historic mean through most of the year. Pershing says "marine heatwaves" like that are becoming more frequent, as climate-change drives shifts in global currents, pushing more warm water and less cold into the Gulf of Maine.

"We've seen the Gulf Stream shift further north. The Nova Scotia Labrador current is weaker. So that kind of allows this warm water pool and build up and really push on our region," Pershing says.

In the most extreme warm periods, marine ecosystems in the Gulf are disrupted. Harmful algae blooms proliferate, some traditional fisheries falter, and seabirds raise fewer chicks. More southerly species, such as butterfish, black sea bass, squid, and even seahorses make their way to the Gulf in larger numbers.

But this year seems to have been a good one for some of the Gulf's historic inhabitants.

"The cooler temperatures this spring though June probably set things up pretty well," says Donald Lyons, a senior staffer in the Audubon Society's Seabird Restoration Program, based in Bremen.

Lyons says the type of plankton that flourish at cooler temperatures in the spring are also the most nutritious for small fish, such as herring and sand lance. Healthier populations of those fish, in turn, flow up the food chain to the benefit of higher-level predators such as puffin and tern. That means more food for more baby birds.

“Generally birds were more successful raising chicks, raising young, to fledging age to when they can fly and leave the colony,” says Lyons. “Much more successful than last year, and really probably above average across-the-board."

But the cooling trend in some waters in the Gulf of Maine this year is not apparent well below the surface. And that's had a negative effect on other important species.

"If you look in the deep waters, it’s been one or two degrees warmer than average over the last 12 months," says Nick Record, a scientist at Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences in East Boothbay.

Record studies gulf temperatures at depths of 100 meters and more. He wants to know what's going on with a particular zooplankton that hibernates down there – a rice-sized crustacean called "Calanus finmarchicus."

It's a staple in the diet of the endangered North Atlantic right whale, which have historically feasted in the Eastern Gulf near Maine, when the Calanus begin to hibernate in late summer and early fall.

"That's also when Calanus are the fattiest, because they pack on fats to over-winter,” Record says. “So they, potentially, really are a valuable thing for whales to be eating because they're so fatty. At that time of year, it's more in the eastern Gulf of Maine, and that's when we've seen the big declines in Calanus and also the changes in right whale foraging behavior."

Record says the eastern Gulf's deep water is warming beyond the point where Calanus can hibernate effectively. That leaves them undernourished and less nutritious for the whales. And recently the whales appear to have been bypassing the Gulf's Bay of Fundy, scouting farther north, to Canada's Gulf of St. Lawrence, where whales are discovering Calanus in abundance.

But those expeditions to areas where they were not expected to be have put the whales at higher risk of ship strikes and entanglements. Over the last three years, 20 of the animals – about five percent of their remaining population – were found dead in Canadian waters.

"I think of them like climate refugees,” Record says. “They've had a food resource that they've relied on for years and years and years and that reliability has been one of the keys to successful management."

Further complicating matters, says Andrew Pershing of the Gulf Of Maine Research Institute, is that the relatively cooler surface temperatures in the Gulf seen earlier this year shifted abruptly upward at mid-summer, setting records on some days.

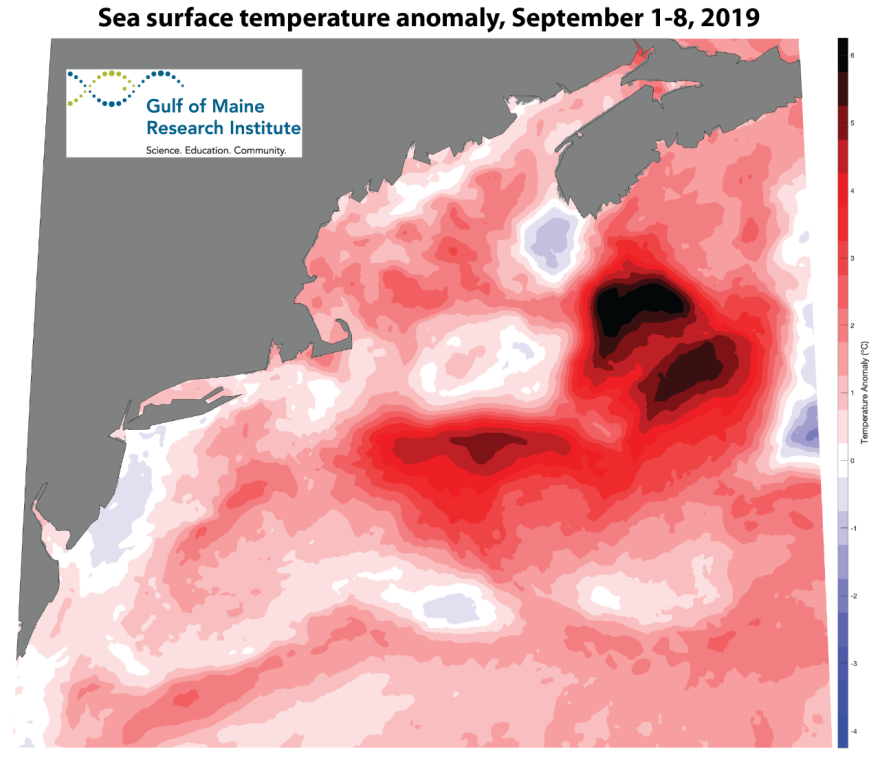

And early in September, he charted a major new development – a 4,000 square-mile blob of water much warmer than the norm.

"This somewhat subtropical water that's sitting off the Gulf of Maine, you can see it in this map."

He points to a black, mushroom-shaped mass to the south-east of Nova Scotia.

"I've added some new colors because we’re seeing more of these conditions where – this is five, six degrees Celsius above normal, which is a really, really big change in the ocean. It’s about ten degrees Fahrenheit."

Pershing says summer-like conditions in the Gulf are lasting a full month longer than they were just 20 years ago.

"Temperatures really popped for us in July, and it's consistent with what we experienced here on land, where I think it was the warmest July ever we've had in Maine."

This story is part of a week-long reporting project Covering Climate Now by Maine Public and more than 300 other news outlets around the world. The series comes in advance of the United Nations Climate Action Summit on Monday Sept. 23 in New York. More information here.

Originally published 4:19 p.m. Sept. 18, 2019