A long simmering debate over Skowhegan High School's use of an ‘Indian’ mascot is once again headed for a showdown.

Three years after the local school board rejected calls to retire it, leaders from the Penobscot Nation and other Maine tribes are asking the board to reconsider, saying it's offensive. But the small town's identity is closely associated with native history, even though nearly all of its residents are white, and part of that history includes the bloody massacre of more than 150 Native Americans by colonial British troops.

The massacre at Norridgewock, which occurred just a few miles from Skowhegan, pitted the French against the English over contested lands occupied by native Maine tribes. The British wanted the fertile farmland to expand New England settlements; they also wanted to capture or kill Father Sebastian Rasle, a Catholic priest who befriended the Abenaki people. In August of 1724, 200 troops launched a surprise attack on their native village on the banks of the Kennebec River. Father Rasle was the first of many casualties.

"And they were shooting everybody, women and children, and then taking their scalps. Everybody that was dead, they were taking their scalps. The river ran red with their blood," says Barry Dana, a former chief of the Penobscot Nation.

Dana learned, growing up, that one of his ancestors had survived the massacre and, along with other survivors, sought refuge on an island in the Penobscot River which eventually became the Penobscot reservation.

The towns of Skowhegan and Norridgewock, meanwhile, have sought to embrace their local history by keeping their native names. Skowhegan, according to one translation, means "watching place for fish." The town is home to what's been called "World's Tallest Indian," a 62-foot sculpture of an Abenaki man, carved by the artist Bernard Langlais and dedicated in 1969 to "the first people to use these lands in peaceful ways."

"When I think of the name ‘Skowhegan Indians,’ I think of pride, honor and a great love for my community, where I was born," says local resident Judi York.

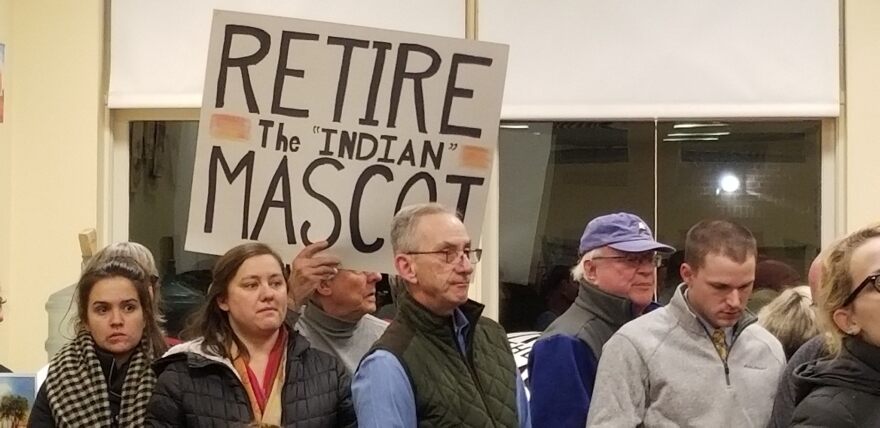

York, who is not Native American, spoke at a packed school board meeting Thursday night. She said she feared that ending the use of the Indians mascot would lead to erosion of the town's cultural identity.

"Our town name is an Indian word,” she said. “Do we have to change that? Our town logo brand is an Indian fishing. A person fishing should not be an offense. Do we have to change that? Our town even commissioned a famous artist to build a sculpture to honor our heritage. Shall we burn that down?"

Tribal leaders say the town's name, its seal and its statue are symbols that are distinctly different from the dehumanizing use of the high school's mascot, especially in a school district that has only a dozen Native American students left. And while white students at Skowhegan High School are divided about the issue, senior Adelle Bellanger says she is embarrassed by the mascot, the last one of its kind in use in Maine.

"I went to Girls' State over the summer, which was a wonderful experience,” she says. “However when I told people that I was from Skowhegan, I had — not the response I expected from some people. They frequently brought up the mascot and even mentioned, like, that the town was racist and whatnot."

Senior Bailey Weston says "I don't think that we really need the Indian to feel a sense of pride in our community."

And, Weston says, if members of the Penobscot Nation finds the mascot offensive, then it's disrespectful for the community not to honor their wishes.

But recent high school graduate David Grace says that the school has already eliminated an Indian caricature and other imagery associated with the mascot. He told the board he doesn't want to give up the Indian name entirely.

"You guys are asking us more and more and more. It's not good for the community," Grace says.

For more than a decade, the American Psychological Association has recommended the immediate retirement of Native American mascots, symbols, images and personalities by schools athletic teams and organizations, saying they perpetuate racist stereotypes and deny Native American people control over their own definitions.

Skyler Lewey, a 15-year-old member of the Penobscot Nation from Indian Island, says that the white students who who call themselves "Indians" have not experienced life on a reservation.

"You guys do say you celebrate the heritage and the culture, but you don't,” says Lewey. “You don't have socials. You don't have ceremonies...you guys are only Indians for four years, and we're Indians for life."

"They carry the inherited historical trauma of a bloody massacre in our own backyard, which will not be forgotten by them, and should not be forgotten by us," says Dr. Susan Cochran, a family physician from Skowhegan.

Cochran says that after Thursday night's meeting, she doubts many area residents know the history of the Norridgewock massacre or understand how it might be perceived by Abenaki descendents today. Every year the Penobscot people hold a ceremony recognizing the traumatic event. It's something former Chief Dana says he could "feel in his bones" the first time he visited the site.

MSAD 54 has planned a public forum on the mascot issue for January 8.

Originally published 5:37 p.m. Friday, December 7, 2018.