AUGUSTA, Maine - Like so many states, Maine is in the grip of an opiate epidemic that shows no signs of slowing down. While other states have expanded drug treatment as part of the response, Maine has not. There are fewer treatment options than just a few years ago. Republican Gov. Paul LePage is pursuing a drug enforcement strategy instead. Critics say that's taking a heavy toll.

A major blow came in May when one of Maine's largest treatment providers announced it was closing. Mercy Recovery Center placed much of the blame on cuts in state funding. There was already a shortage of long-term residential treatment beds. And then, last week, a methadone clinic in southern Maine also announced it was shutting its doors.

For those who want to safely get off heroin the first step toward recovery is often detox - if you can get in. "Yesterday we had someone count and we had turned away 113 people this month because the program was full," says Lauren Wert.

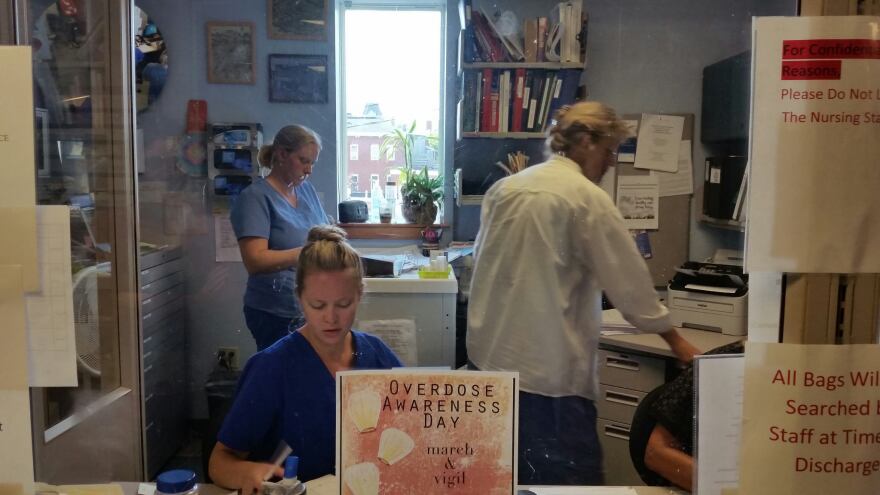

Wert is the director of nursing at Milestone Foundation in Portland. This is the epicenter of the heroin crisis in Maine, and Milestone is the only residential detox around. It has just 16 beds available for three-to-seven-day stays.

At the small nurses station, Wert says she and her staff gently inform a steady stream of callers that they can't help them out. "Often times people cry," she says. "Sometimes the client is so frustrated that they've given up calling, but the family member will continue to call for them. They're asking questions like, 'Where else do we go? What do I do? He feels like he's going to die.' "

Wert says there used to be places to refer clients, but now all the staff can say is, "I'm so sorry."

"It's frustrating not to be able to get people services who desperately want it," says Dr. Mary Dowd, the medical director for Milestone. Dowd says the challenge is that most heroin addicts can't get sober without replacement medications like methadone and Suboxone. At a roundtable discussion in Maine earlier this week, U.S. Drug Control Policy Director Michael Botticelli said increasing access to them, in Maine and elsewhere, is essential because they work.

"People on medicated assisted treatment stay in treatment and they don't die and they don't get infectious diseases as a result of their injection drug use issues,"Botticelli said.

But in Maine, there are long waiting lists for methadone and Suboxone, even for those who have insurance or money to pay for treatment out of pocket. For those who don't, Dowd says the only other options are the ER, jail or to try to score a short-term stay at Milestone. "And it's not treatment. It's detox," she says. "They get the drugs out of their system but then they don't get treatment so they have to keep coming back and back and back."

"I've probably been here 10 times in the last six months, probably," says Eric Brewer. Brewer is 37 years old. He's a longtime heroin addict who spent time in prison on a drug trafficking conviction. He says he stayed sober for more than five years, but eventually relapsed and wound up at Milestone. "Luckily, this time things fell into place for me and I have someone who volunteered to pay for my first month in a sober house."

Brewer has no insurance and no money to pay for long-term residential treatment. And he's hardly alone. Two years ago the state dropped hundreds of single adults from state Medicaid rolls. Under the leadership of Gov. LePage, Maine refused to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act and set caps on the length of time Medicaid patients receive drug treatment.

Dr. Vijay Amarendran oversees methadone and Suboxone services at Acadia Hospital in Bangor. "We need to provide more insurance coverage for people, not less insurance coverage," Amarendran says. "Clearly, that doesn't make sense."

Treatment providers and law enforcement personnel told Director Botticelli that what they really need is more federal funding for treatment and recovery.

Gov. LePage says he's satisfied with the $72 million spent on drug treatment in the state. What concerns him more, he says, is how little is spent on drug enforcement. He's frustrated that Democratic lawmakers have not agreed to hire more drug agents. In a recent radio address he proposed using the Maine Army National Guard for that purpose. "We must provide solutions on how to disrupt the drug supply and hunt down the traffickers."

Critics say that's a misguided strategy at a time when members of law enforcement are confronting heroin addicts overdosing on the side of the road. We can take them to the hospital, said Lt. Hartley Mowatt of the small town Paris Police Department, but after a couple of days they get released to the streets and do it again "because there's no other places there to give them help. And that's what the problem is."